Top Stories

If you attended Grad Slam 2016, you already know Sara Weinstein as the Raccoon Girl from her talk about parasite transmission in raccoons. But do you know how she went from chemistry and art to majoring in biology and how her skills in mouse stuffing have helped her career in EEMB?

If you attended Grad Slam â2016, you might already know Sara Weinstein as the Raccoon Girl from her talk about parasite transmission in raccoons. Or, if you play ultimate frisbee in Santa Barbara, you might know her as a teammate. Or, if you've lived in âthe area long enough, you might remember her art from past I Madonnari chalk festivals.

If you attended Grad Slam â2016, you might already know Sara Weinstein as the Raccoon Girl from her talk about parasite transmission in raccoons. Or, if you play ultimate frisbee in Santa Barbara, you might know her as a teammate. Or, if you've lived in âthe area long enough, you might remember her art from past I Madonnari chalk festivals.

I sat down with Sara, a doctoral student in Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology (EEMB), to find out more about her raccoon research, her secrets to a successful life as a graduate student, and how she went from pursuing art to pursuing parasites.

What would people be most surprised to know about you?

I started undergrad at UC Berkeley planning to double major in Practice of Art and Chemistry. But it only took one quarter to realize I wasn't cut out for either. I could translate what I saw onto paper but that made me an illustrator, not an artist. And after half a semester of chemistry, the first lecture that truly interested me was a lecture on plant-derived chemotherapy drugs.

It was one of those light bulb moments - why should I spend four years hoping they'd mention biology in my chemistry class, when I could major in Biology! In the end, I graduated with a degree in Integrative Biology and a shelf full of beautifully illustrated lab notebooks.

It was one of those light bulb moments - why should I spend four years hoping they'd mention biology in my chemistry class, when I could major in Biology! In the end, I graduated with a degree in Integrative Biology and a shelf full of beautifully illustrated lab notebooks.

How would you best describe your research to someone who wasn't in your field?

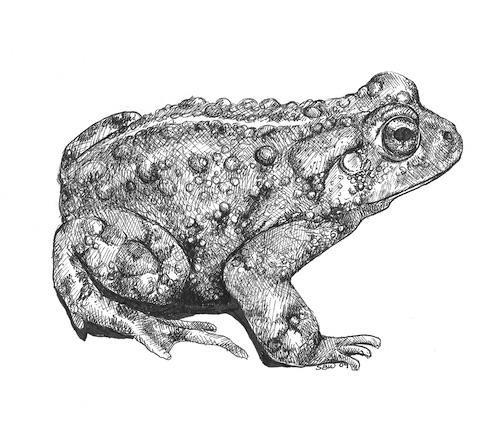

I'm a parasitologist, which is great because everything has parasites. Parasites are a natural part of healthy ecosystems, but humans are constantly changing how hosts and parasites interact with one another. Broadly, this is what I study, both in our local wildlife and in Africa.

Here in Santa Barbara, my dissertation focuses on transmission dynamics of raccoon roundworm, a 15 cm long nematode that matures in raccoons, but can also infect rodents, birds, and humans. I've spent the last couple of years looking at infection patterns in raccoons, parasite spillover into rodents, and disease risk in people.

How is project raccoon going? How can people get involved?

How is project raccoon going? How can people get involved?

I am wrapping up the raccoonâ-and-rodent phase of the project. After dissecting more raccoons then any person should, I now know that 80% of local raccoons are infected and, more importantly, if roadkill smells on the road, it will smell even worse in the lab.

Raccoons are full of worms and rodents are full of worms. But, what about humans? Like many parasites, this raccoon worm can cause severe disease in humans, but fortunately, it's incredibly rare. Despite our constant exposure to raccoons, there is less than a single diagnosed case per year.

We are now in the final phase of "Project Raccoon," recruiting volunteers who want to be tested for exposure to this wildlife parasite. Anyone who has lived in Santa Barbara County for at least three years is welcome to join the study! Participants fill out a consent form and a questionnaire, and then provide a small blood sample. Each person who participates helps us better understand the risks associated with this parasite, gets an Amazon gift card, and receives an awesome Project Raccoon sticker.

Anyone interested in getting tested for raccoon parasite exposure can email me at SBParasitology@gmail.com!

What advice would you give to an incoming graduate student?

The first thing I would say is that it's okay to fail sometimes. Projects that don't work are part of the process, but you have to commit to every attempt because you never know what's going to succeed.

My dissertation is about mammal parasites, but I spent my first year attempting to work out the life cycle of an obscure octopus parasite. Parasitologists have been trying to solve this riddle since the 1800s. The last attempt was in 1954, so I thought it would be fun to try again with our new shiny molecular tools. It started out great, the PCR primers worked and I had hundreds of cannibalistic baby octopuses crawling all over the lab. But three months in to the experiment, the octos sprouted yellow tentacle fuzz and within weeks that bacterial infection wiped out the entire colony.

My dissertation is about mammal parasites, but I spent my first year attempting to work out the life cycle of an obscure octopus parasite. Parasitologists have been trying to solve this riddle since the 1800s. The last attempt was in 1954, so I thought it would be fun to try again with our new shiny molecular tools. It started out great, the PCR primers worked and I had hundreds of cannibalistic baby octopuses crawling all over the lab. But three months in to the experiment, the octos sprouted yellow tentacle fuzz and within weeks that bacterial infection wiped out the entire colony.

Although the project didn't work out, I don't regret working on it. I learned how to design PCR primers and those hatchling octopuses ended up being a critical component of another graduate student's research.

The second bit of advice would be to collaborate. I think everyone ends up ahead when we share skills, knowledge, and even samples. I've got extra raccoon worms I'd be happy to share...

Speaking of advice, you recently reached the finals at the Grad Slam 2016. What advice would you have for people doing it next year?

Enter the competition! There are so many students doing such cool research at UCSB, and Grad Slam is a great opportunity to share it with everyone. And hey, it's just three minutes, so you can slap something together in only 30 hours.

What is your favorite thing you do to relax?

I play a lot of ultimate frisbee. I've been accused of graduating from Berkeley with a major in biology and a minor in frisbee. I don't play on a competitive team anymore, but there are quite a few great pick-up games in town.

What is your most memorable research experience and why?

I was part of a research expedition in Kenya and the conditions were really tough. We were camping at 13,000 feet, my boots froze solid every night, and my microscope broke in half when our shelter collapsed in a hail storm. We'd been up there for several weeks when the National Geographic photographer and writer made it up to our camp.

By that point, the microscope was duct-taped back together and we'd had enough time to turn the new shelter walls into our own personal Swahili dictionary, scribbling words onto the tarps with a sharpie.

One afternoon, we were taking a hand-thawing tea break and explaining the logic behind our ludicrous rodent trap line names (e.g., "The stinky stream dream line") and the writer asks if we've read "The Martian." "Of course." To which he responds, "You remind me of Mark Watneyâ." What a compliment! Although, in retrospect, we might just have been starting to smell like a guy stuck alone on Mars for two years.

One afternoon, we were taking a hand-thawing tea break and explaining the logic behind our ludicrous rodent trap line names (e.g., "The stinky stream dream line") and the writer asks if we've read "The Martian." "Of course." To which he responds, "You remind me of Mark Watneyâ." What a compliment! Although, in retrospect, we might just have been starting to smell like a guy stuck alone on Mars for two years.

What is a major influence that has helped shape who you are today?

As an undergrad, I had several incredible mentors at the UC Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ). The Museum does a fantastic job of involving students in research, particularly in the museum prep lab. For those not familiar with natural history museums, the prep lab is where you prepare the specimens for the permanent museum collection. It's basically museum-flavored taxidermy and at the MVZ, anyone could learn how to stuff a rodent.

Of all the things I learned in undergrad, mouse stuffing was what landed me my first research job after graduation. I spent the summer surveying rodents throughout Northern California, and the animal trapping and handling skills I learned there have been instrumental in my Ph.D. research here.

What do you hope to be doing 5 or 10 years out of graduate school?

Exciting science in interesting places! Already I feel incredibly lucky to be able to spend my time asking questions, solving puzzles, and traveling the world. Sure, there are days when the code breaks, experimental results don't make sense, or skunk guts get spilled all over the lab bench. But, overall, science is awesome and it's what I want to do for the rest of my life.